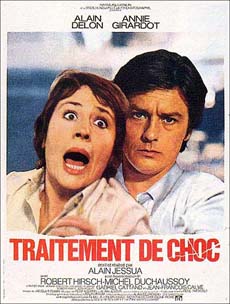

BR: Shock Treatment / Traitement de choc (1973)

Film: Very Good

Film: Very Good

Transfer: Excellent

Extras: Very Good

Label: Severin Films

Region: A

Released: October 27, 2020

Genre: Thriller / Horror / Suspense

Synopsis: A businesswoman visits a health clinic with highly unconventional treatments to tackle the physical and emotional quirks of aging.

Special Features: 3 Interview Featurettes: “Alain Jessua: The Lone Deranger – Interview with Bernard Payen, curator at the Cinematheques Francaise”(20:12) + “Koering’s Scoring – Interview with composer René Koering” (23:44) + “Doctor’s Orders – 2007 Interview with Alain Jessua” (9:50) / “Drumrunning: René Koering commentary on 3 sequences” (8:18) / Theatrical Trailer.

Review:

It’s a little challenging to define Alain Jessua’s odd little thriller, which is neither a full horror film nor blatant satire of chi-chi health clinics catering to the wealthy with desires to stave off as much of the aging process as possible, but his clever melange works fairly well, especially as a barbed rumination by an auteur with roots in the French New Wave.

Former Rocco and His Brothers (1960) co-stars Alain Delon and Annie Girardot reunite as inevitable foes in what unfolds as a woman, Helene (Girardot), who takes the advice of a close friend and tries an intensive getaway in which patients submit to a team of doctors supposedly skilled in unusual sea-based, organic treatments.

Helene has a few weeks to decide whether to sign away her freedom and follow Dr. Deviler’s strict, peculiar treatments – some intimate, others experienced with the modest but tightly-knitted group – but she also notices the health and sanity of the clinic’s Portuguese hired hands may suggest ghoulish behind-the-scenes actions by the reserved doctors.

Delon’s innate coldness suits Devilers, a self-styled guru who wafts between a supposed interest in helping his patients; a constricted playboy who fell into a niche career by chance; and a hypocrite whose contempt for his rich clients is frequently palpable.

Shock Treatment has some tonal similarities to Robin Cook’s 1977 novel Coma, itself rendered into a creepy film in 1978 by Michael Crichton, in which a heroine suspects grisly malfeasance at a teaching hospital, and where various levels of the staff are involved in a finely honed cottage industry involving murder. But Jessua’s approach, while largely linear, is told with modernistic jump cuts; a Bossa Nova score composed by classical composer René Koering (with input by Jessua, in terms of some instrumentation, vocals, and percussion); and Jacques Robin’s lush, pastel-rich cinematography, which exploits the coarse French coastal town where Devilers’ patients reside for undetermined stretches.

Belgian poster with a running Little Delon in his birthday suit.

The elite clients participate in group sessions of Thalassotherapy, which involves sauna, seafood, seaweed baths & slatherings, and skinny dipping in the ocean – the latter showcased in a lengthy sequence where the group beckon a passing Devilers to join. Shock has several frank bouts of nudity, but it’s the moment when Delon undresses and joins his coed troupe which continues to earn the film its notoriety, where men and women frolic full frontal in the crashing waves, including Delon.

It’s also a sequence where Koering (and Jessua’s) score finally clicks with viewers who might be a little puzzled by the director’s idiomatic choice. (As he details in Severin’s lengthy composer interview, Koering was also familiar with Bruno Maderna, who wrote a Bossa Nova score for Giulio Questi’s batshit crazy 1972 giallo Death Laid an Egg.)

The main theme goes through several subtle incarnations which, as Koering notes in a trio of selected scene commentaries, comment directly on the Portuguese workers, the patients’ self-serving glee in following Devilers’ treatment, and Helene’s gradual discovery of the clinic’s secret sauce, so to speak.

Jessua does move the camera throughout the film, but it’s Helene Plemiannikov’s invisible editing which transforms blatant jump cuts into seamless transitions and natural scene beats, such as when Helene arrives at the clinic and examines her room; the odd consults and sessions with nurses and doctors; social bonding with the vain, long-term clients; and when she begins sleuthing throughout the clinic and Devilers’ home. Whereas Franco Arcalli’s modern editing in Egg shaped the puzzle mystery into a series of impressions and teases, Plemiannikov and assistant editor Catherine Dubeau stick with the linear plot, nudging and leaping through character movements and scenes yet keeping the perspective from Helene’s vantage as she advances from a position of client to patient, and snoop to potential victim – very much like Crichton’s denouement for Coma.

Jessua’s film may need a second viewing to absorb both the subtext within the film, and especially the deliberate ambiguities which film historian Berard Payen affixes to the auteur – the latter a quality that reportedly runs throughout Jessua’s rather modest filmography.

It isn’t a leap to cite Shock as an early medical thriller, where outlandish and rather cultish behaviour is exposed when an innocent is lured, joins, or discovers grisly subterfuge. One aspect might evoke the legend of Elizabeth Báthory‘s bathing in the blood of virgins which, like Jessua’s story, has vampirical elements, but the clinic’s mandate is to enforce an organized (and supposedly successful) effort for its clients to remain young or freeze the aging process, and maybe achieve a superior, super-human transformation.

It isn’t a leap to cite Shock as an early medical thriller, where outlandish and rather cultish behaviour is exposed when an innocent is lured, joins, or discovers grisly subterfuge. One aspect might evoke the legend of Elizabeth Báthory‘s bathing in the blood of virgins which, like Jessua’s story, has vampirical elements, but the clinic’s mandate is to enforce an organized (and supposedly successful) effort for its clients to remain young or freeze the aging process, and maybe achieve a superior, super-human transformation.

Jessua’s film may not offer wholly new elements to genre connoisseurs, but his roots in the French New Wave certainly give the story a modern texture, and perhaps demonstrate a highly efficient method of stripping a thriller to its meatiest elements, packaged in a taut 87min. running time.

Severin’s Blu-ray release comes in a standard single disc release, and a limited edition with alternate sleeve art and CD featuring the original score in stereo. The transfer flatters the ravishing cinematography, and one has the option of the English dub track and the original French track.

The aforementioned interview with Koering is hugely informative, mostly because Koering is a natural raconteur who contextualizes his entry into concert composition, his brief divergence into movies, scoring a quartet of Jessua films and a few silent film concerts, and his preference for composing in solitude – free from the shackles of dialogue, redubbing, editing, and mixing in films.

Payen’s separate portrait of Jessua is both an overview (and intriguing tease) of the writer-director’s best-known and rarely-seen films, and it sets up the archival 2007 interview with the filmmaker who later switched to his other love, writing novels, after directing his final film in 1997.

Alain Jessua died in 2017, but his filmography as director include the short Léon la lune 1956), and the feature films La vie à l’envers (1964), The Killing Game (1967), Traitement de choc(1973), Armaguedon (1977) with Alain Delon, The Dogs (1979), Paradis pour tous (1982), Frankenstein 90 (1984), En toute innocence (1988), and The Colors of the Devil (1997).

In addition to Jessua’s 6 subsequent films, Hélène Plemiannikov’s extensive editing credits include Roger Vadim’s segment of Spirits of the Dead (1968), and Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) and That Obscure Object of Desire (1977).

© 2021 Mark R. Hasan

External References:

Editor’s Blog — IMDB — Soundtrack Album — Composer Filmography

Vendor Search Links:

Amazon Canada

— Amazon USA

— Amazon UK

Category: Blu-ray / DVD Film Review

Connect